Neutering in Dogs

SPAYING

Neutering a female animal is referred to as spaying. Spaying or ovariohysterectomy involves removal of the womb and ovaries to prevent ‘heats’ and unwanted pregnancies.

Benefits:

• Prevents them from coming into season (usually happens approximately every 6 months) and becoming pregnant

• Prevents them from coming into season (usually happens approximately every 6 months) and becoming pregnant

(*Did you know? A female dog can have up to 12 puppies in a single litter!)

• Prevents false pregnancy – this commonly occurs in female dogs when, after a ‘heat’, the body (and sometimes her mind) think that she is pregnant. This can result in lethargy, inappetance, nausea and even milk production. They may even show nesting behaviours and gather toys into her bed to nurture. This period can be distressing for the pet and owner alike.

• Prevents pyometra (womb infection) – this is a life threatening condition in dogs in which the womb gradually fills up with pus which can eventually lead to septicaemia and death.

• Reduces the risk of mammary (breast) cancer – many older females develop mammary cancers which can be malignant or benign. These usually require surgery to remove to reduce the risk of spread around the body which can be life threatening. Spaying at a young age reduces the risk of mammary cancer dramatically.

Disadvantages:

• Spayed females need fewer calories than unneutered females – this does not mean that all spayed females should be allowed to become overweight! With the correct balance of exercise and nutrition we can easily maintain an optimal body condition

• Spayed females have a slightly higher risk of urinary incontinence in later life, though this can occur in unneutered females too. It is uncommon but usually can be managed very easily with medication.

When do I spay my dog?

We are happy to discuss the individual needs of your dog to decide the optimal time to spay her. In general we recommend:

• For small/medium breeds to be spayed at 6 months before their first season.

• For large breed dogs (>25kg) we usually wait until they are skeletally mature (approximately 1 year old)

• If your dog comes into season then the ideal time to spay her is 3 months later. This allows the hormones produced during her season to return to normal.

CASTRATION

In view of the large numbers of unwanted dogs and dogs euthanased in rehiming centres every year, the number one reason to recommend routine castration of all male dogs is the prevention of breeding and unwanted puppies.

When dogs are carefully minded, so there is no chance of an unplanned mating (or of chasing sheep or cars.) then population control is a less important concern than is the health and welfare of each animal.

We therefore prefer to have a discussion about the pros and cons of castration for each individual as our recommendation on when or whether to castrate will vary depending on the breed, age, temperament and circumstances of each dog. This discussion will typically be at the free six month old puppy health check appointment.

Castration and health

Recent research suggests that castration might increase the risk of some health problems in male dogs (e.g. weight gain, certain cancers, cruciate rupture) while it reduces the risk of others (e.g. testicular tumours, prostate enlargement). There is not currently enough evidence to know how reiable these findings are.

Recent research suggests that castration might increase the risk of some health problems in male dogs (e.g. weight gain, certain cancers, cruciate rupture) while it reduces the risk of others (e.g. testicular tumours, prostate enlargement). There is not currently enough evidence to know how reiable these findings are.

It may be necessary to castrate your dog later in life if he develops prostatic enlargement, prostatiis or testicular tumours. This is generally curative.

Castration and Behaviour

This information is provided by the Association of Pet Behaviour Counsellors.

Castration involves removal of both testes, the main source of testosterone in males. Testosterone acts as a behaviour modulator: it does not directly cause behaviours, but increases the likelihood that certain behaviours will occur, including:

• Escaping/roaming to find in-season bitches

• Urine marking

• Confident aggression to other male dogs

• Excessive mounting of bedding, people, other dogs

Testosterone can also influence other behavioural traits, increasing:

• “Risk-taking” behaviours: entire animals may be more likely to engage in a risky situation rather than withdrawing.

• Arousal and intensity of aggression shown during a conflict: entire males tend to become aroused more quickly, show higher arousal levels and remain aroused for longer than castrated males.

• “Self-confidence”: research in other species suggests that testosterone is associated with confidence and castration with an increase in fearfulness/anxiety. This has not been adequately researched in dogs.

• Interest in other dogs, especially bitches, making it harder to get their focus when working/training.

The longer term effects of castration before puberty compared to afterwards on the development of social behaviour in male dogs have not been fully evaluated and again, more research is needed before we can assess this more accurately.

Whether or not castration will affect the likelihood of a dog showing a particular behaviour will depend on a number of things including:

• Whether or not that behaviour is influenced by testosterone: many problem behaviours are not influenced by testosterone at all, and some of those that are, such as mounting or urine marking, can occur for other reasons including frustration or anxiety.

• How long the dog has been showing the problem behaviour: learning increases the likelihood of a dog continuing to show a particular behaviour after castration.

Castration most likely to be beneficial in:

Dogs showing behaviours that are likely to be influenced by testosterone esp:

◦ Escaping/ roaming/ distractibility due to nearby in-season bitches

◦ Indoor urine marking

◦ Confident aggression to other male dogs (particularly entire males)

◦ Excessive mounting of bedding, people, other dogs

NB: castration can reduce the severity of these behaviours but may not completely eliminate them; behaviour modification may also be needed.

Castrating sooner rather than later should reduce the effect learning has in maintaining behaviours longer term, and castration before puberty should reduce the likelihood of these problems occurring, although it does not always prevent them altogether.

• Dogs that live with or near entire bitches and become very frustrated when they are in season and/or if there is any risk of unwanted mating.

Castration MAY be beneficial in:

• Aggression between two entire male dogs that live together: castration of one or possibly both of the dogs can potentially help to reduce tension between them but ONLY if done alongside BEHAVIOUR MODIFICATION, and ONLY after the dogs have been assessed carefully by a qualified behaviourist before castration is considered.

• Dogs showing aggression that does not seem to be motivated by fear, but ONLY if done alongside BEHAVIOUR MODIFICATION to address the reason why the dog is showing aggression (advise behaviour consult before castration).

Castration unlikely to be beneficial (or detrimental) in dogs showing:

• Unruly, over-excitable adolescent behaviours: these will respond better to reward-based training and appropriate mental and physical stimulation.

• Inappropriate predatory, hunting or herding behaviours e.g. chasing inappropriate targets, digging etc.

Castration could potentially be detrimental in dogs that are generally fearful/unconfident or specifically fearful of unfamiliar people, places and being handled:

There are many anecdotal reports of fearful dogs becoming even more fearful after castration. This could be related to the effect of losing testosterone on their self-confidence, although more research is needed to verify this. This could also occur as a result of aversive experiences associated with castration itself.

• These dogs might benefit from being left entire if showing no testosterone-related behaviour problems, and if unwanted mating can be reliably prevented.

• If castration is necessary for behavioural reasons or to prevent unwanted mating, behaviour modification to reduce fearfulness should ideally be implemented first.

• Care should be taken to make the experience of being castrated as minimally aversive as possible for a fearful dog:

What to do if you are not sure whether to castrate or not?

Deslorelin (Suprelorin, Virbac) is currently the best reversible indicator of the effect of castration and can be used to assess the potential behavioural effects of surgical castration from 4-6 weeks post-implantation.

NB Testosterone initially increases for 2 weeks after implantation and then falls to post-castration levels after 4-6 weeks.

Caroline Warnes BVSc MSc CCAB MRCVS May 2015

References available on request: cwarnesbehaviour@googlemail.com

This is a highly contagious, potentially fatal viral disease. It is spread through infected faeces and can survive in the environment for several years. Symptoms include severe fever, vomiting and severe diarrhoea.

This is a highly contagious, potentially fatal viral disease. It is spread through infected faeces and can survive in the environment for several years. Symptoms include severe fever, vomiting and severe diarrhoea. Lungworm (Angiostrongylus vasorum) is a parasite that infects dogs. The adult lungworm lives in the heart and major blood vessels supplying the lungs where it causes many problems.

Lungworm (Angiostrongylus vasorum) is a parasite that infects dogs. The adult lungworm lives in the heart and major blood vessels supplying the lungs where it causes many problems. Fleas spend their adult life on the dog or cat, rarely moving from one host to another and feeding by piercing the host’s skin and sucking blood. After feeding for 1-2 days female fleas begin to lay eggs – each flea is capable of producing 20-30 eggs per day!

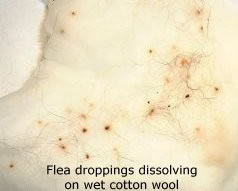

Fleas spend their adult life on the dog or cat, rarely moving from one host to another and feeding by piercing the host’s skin and sucking blood. After feeding for 1-2 days female fleas begin to lay eggs – each flea is capable of producing 20-30 eggs per day! The best way to check if your pet has fleas is to comb their coat out with a fine tooth ‘flea comb’ over a clean white surface so that any fleas or ‘flea dirt’ (flea faeces is digested blood) will fall onto the surface.

The best way to check if your pet has fleas is to comb their coat out with a fine tooth ‘flea comb’ over a clean white surface so that any fleas or ‘flea dirt’ (flea faeces is digested blood) will fall onto the surface. • Prevents them from coming into season (usually happens approximately every 6 months) and becoming pregnant

• Prevents them from coming into season (usually happens approximately every 6 months) and becoming pregnant

Recent research suggests that castration might increase the risk of some health problems in male dogs (e.g. weight gain, certain cancers, cruciate rupture) while it reduces the risk of others (e.g. testicular tumours, prostate enlargement). There is not currently enough evidence to know how reiable these findings are.

Recent research suggests that castration might increase the risk of some health problems in male dogs (e.g. weight gain, certain cancers, cruciate rupture) while it reduces the risk of others (e.g. testicular tumours, prostate enlargement). There is not currently enough evidence to know how reiable these findings are. This number can be read by a scanner. The microchip is injected through a sterile needle under the pet’s skin between the shoulder blades.

This number can be read by a scanner. The microchip is injected through a sterile needle under the pet’s skin between the shoulder blades. When buying your pet insurance, take the time to choose the right policy because if you buy the wrong policy it can be very difficult to change to a better product later on. Here’s how to choose the right policy:

When buying your pet insurance, take the time to choose the right policy because if you buy the wrong policy it can be very difficult to change to a better product later on. Here’s how to choose the right policy: 1. Your pet needs an ISO standard identification microchip. This can be done any time before a rabies vaccination or even on the same day, but it must be before the vaccination.

1. Your pet needs an ISO standard identification microchip. This can be done any time before a rabies vaccination or even on the same day, but it must be before the vaccination. This will include some important questions about your pet’s health and will take a few minutes to read and complete. Ensure we have a contact phone number for the day.

This will include some important questions about your pet’s health and will take a few minutes to read and complete. Ensure we have a contact phone number for the day.